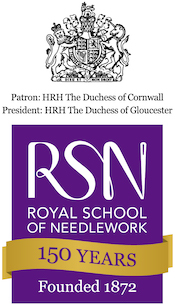

Explore the captivating tale behind an Edwardian embroidered tablecloth in the RSN Collection with RSN volunteer Jo Morris. This signature tablecloth, with its more than 215 signatures, illustrates through stitch a network of family, friends, and celebrities in Oxford, London, and much further afield.

From an American opera singer to an Irish peer and a Breton folk singer, each signature holds a unique story, offering a glimpse into the social fabric of the time. This blog post sheds light on the cultural phenomenon of autograph hunting and the vibrant personalities who left their mark on this exceptional survival.

Jo Morris is a volunteer at the Royal School of Needlework, where she assists in the digitisation and cataloguing of the collection.

What did an American opera singer, the editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, a member of the Indian Muslim League, an Irish peer, and a Breton folk singer have in common? The answer is that they were all friends or people of interest to the Rose family of Oxford in the Edwardian era. They feature on a tablecloth displaying hundreds of embroidered ‘autograph’ signatures, made between 1901 and 1905 and now in the RSN Collection.1

The tablecloth was probably made by Gertrude Mabel Rose, who has neatly encircled her own name and the date 10th November 1901 in red in one corner, perhaps when she began the embroidery. There are twenty-five signatures of the extended Rose family of North Oxford.

The father, Thomas Henry, was a draper, a governor of the local hospital, and a Justice of the Peace. Gertrude Mabel later married Otto May from London, son of a German émigré merchant. Otto signed her tablecloth while he was a medical student, as listed in the 1901 census, but had become a doctor by their marriage in 1912. The parish register marriage entry displays the couple’s signatures much as they are found on the earlier tablecloth.2

The tablecloth is a square of ecru linen featuring signatures embroidered in a variation of backstitch, in black silk for men and red for women. Those of a couple are often ‘crossed’. It has a neat scalloped edging of black buttonhole and red whipped chain-stitch (or possibly a form of ‘Kensington outline stitch’ which was popular in the USA).

Though it isn’t technically complicated, it is a ‘tour de force’ with over 200 signatures in recognisably distinct hands. These were either written directly onto the cloth or traced from another source. A few names show some of the pencil signature which has been stitched over. Some have accompanying dates and locations, and two commemorate members of the Rose family who had recently passed away, which definitely suggests reproduction by tracing. Three script inscriptions written in Arabic, Farsi, or Urdu are rather inaccurately stitched.

Very often the stitches on a piece of historical embroidery have to speak for themselves. We may have little or no information about the life or personality of the maker, however beautiful the result. Samplers can provide a name, date, or location, but artefacts of the late Victorian to Edwardian craze for autographs give an equally tantalising glimpse into a ‘moment in time.’ Enthusiasts collected signatures of family and friends, but especially prized were those of any well-known or prominent characters in society.

Autograph hunting became so popular in the USA, Britain, and Europe that there was quite a reaction against ‘Autographomania’ in the press, and among famous individuals who became ‘victims’ of eager collectors’ pursuit.3 Illustrator Henry Furniss complained in the Strand Magazine in 1902: ‘Is there any inoculation possible to avert autograph fever? It is a disease always prevalent in the United States, but of late years has become quite an epidemic in England’.4 Oscar Wilde, according to a biographer, ‘employed three secretaries while travelling through the United States: one to receive flowers; another to sign autographs; and a final unshorn attendant to clip trimmings from his locks’.5

When Gertrude Mabel embroidered her own autograph tablecloth they were a popular trend in Britain. Newspapers all over the country reported the phenomenon, and they became a common feature at local bazaars and fundraising events in the wider community. But what was their attraction? The Graphic Weekly Illustrated of 20th January 1900 stated: ‘The custom of signed tablecloths for special dinner parties is, I hear, likely to be fashionable. That is to say, the guests write their name in pencil, and the autographs are subsequently embroidered in facsimile of the writing, so that, in spite of washing, they become permanent’.6. Over in Coventry, the Herald of 19th October that year describes a London club which ‘now possesses a cloth so crowded with autographs, coats-of-arms, and other devices, that there is but little space left unoccupied’.7

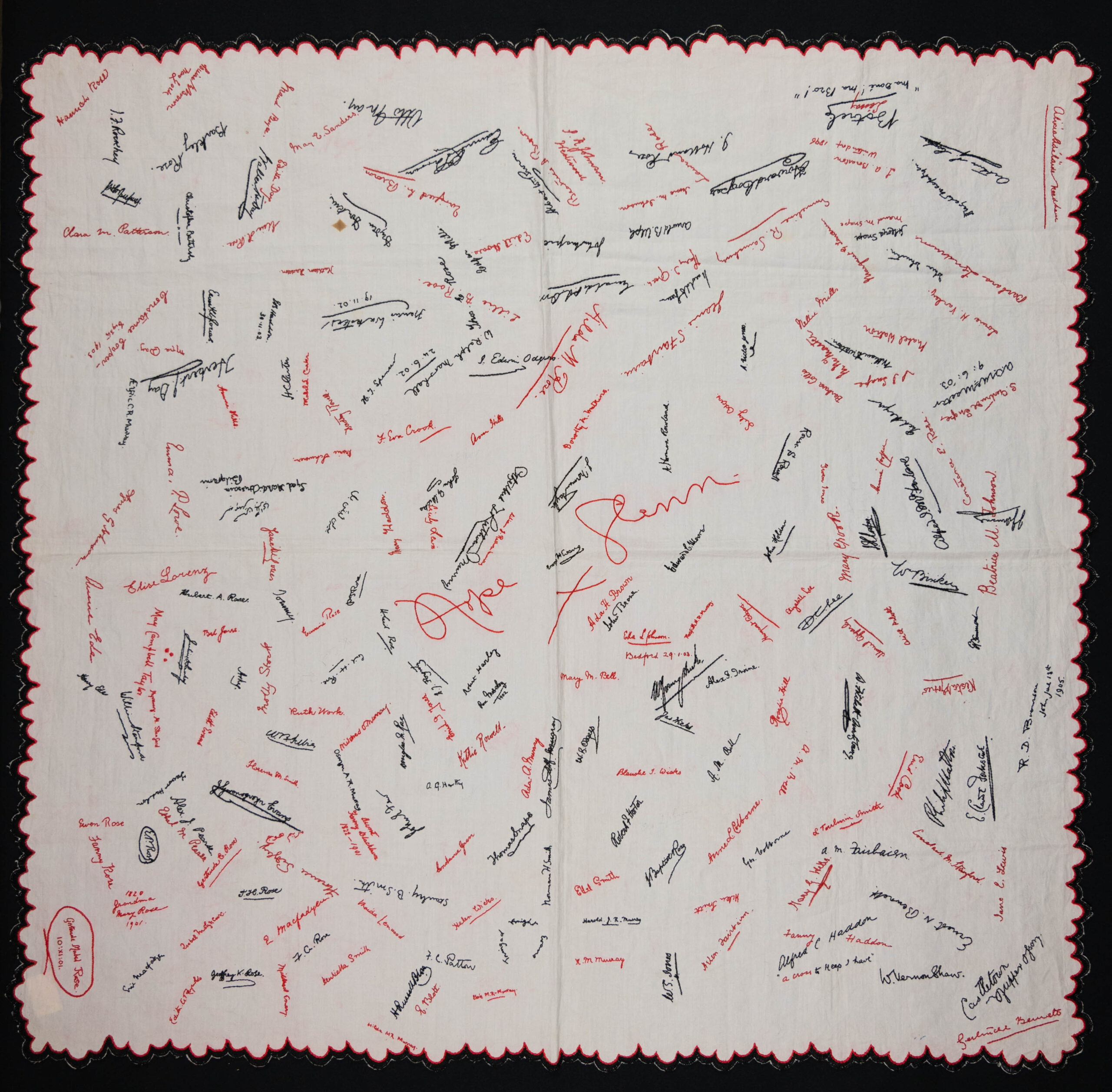

The signatures collected by Gertrude Mabel Rose are a surprisingly eclectic group and we can discover more about some of the two hundred plus names. Her possible friends who signed included Maida Lenwood, aged 19 in 1901. Clearly an intelligent young woman, she’d won an Open Scholarship to read Classics and Philosophy at Somerville College in Oxford that April.

Maida was the daughter of Reverend Walter Lenwood, a non-conformist minister in Nether Hallam, Yorkshire, and had been ‘brought up in an intense missionary atmosphere’ according to a Sheffield press report.10 After five years in Oxford, she qualified as a teacher at Sheffield University, then became a missionary to Madras, India for the London Missionary Society. In 1913 she married Rev. Duncan Leith in India but returned to England after he tragically drowned in a whirlpool on the Indian coast in 1924.11 Also represented on the tablecloth are Oxford’s academia and professionals, among them the extensive Ruthven-Murray family.

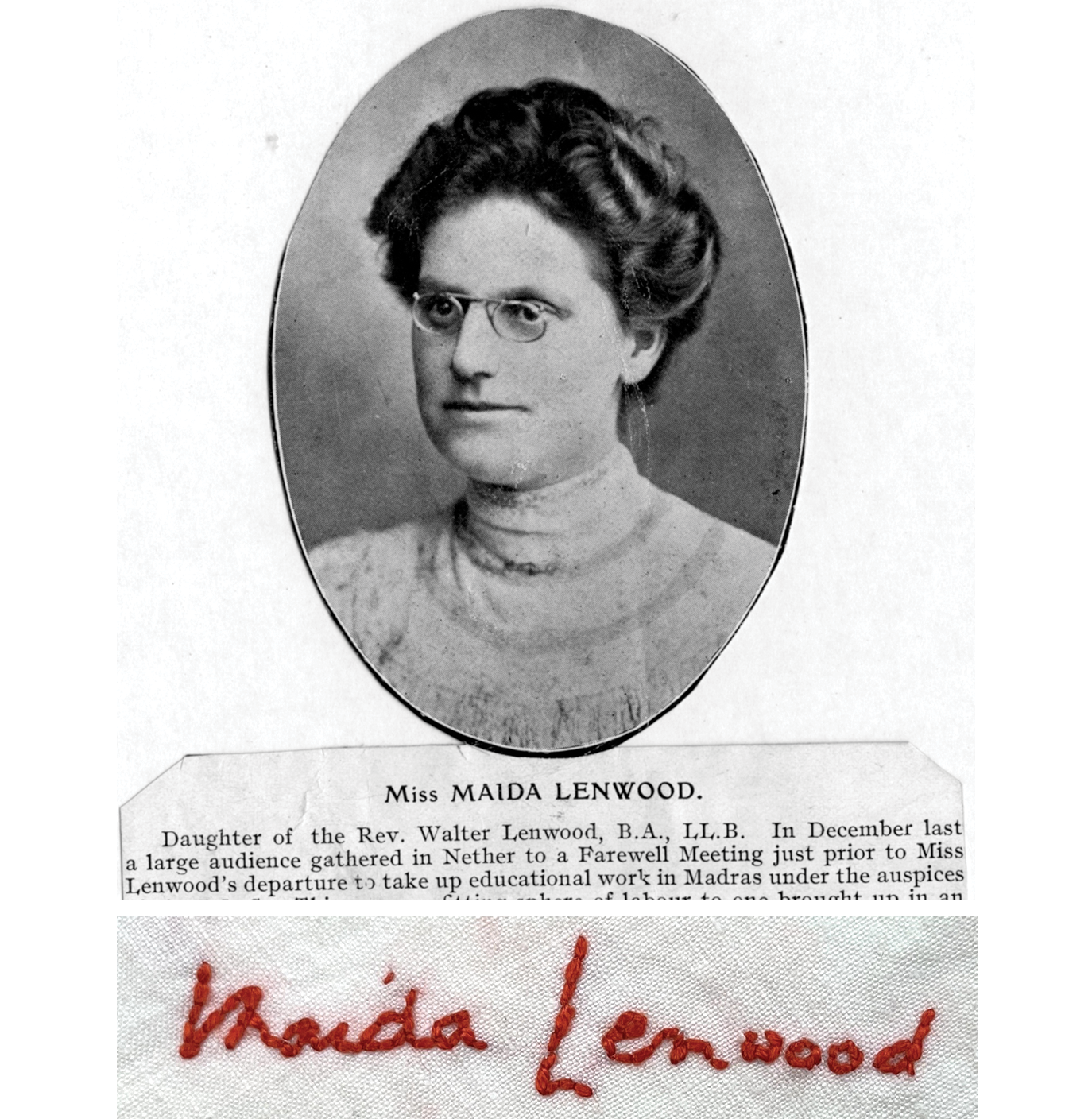

James Augustus Henry Ruthven-Murray was the eccentric Scottish editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. He was a dedicated philologist who knew 22 languages to varying levels of fluency. He’d lived in Oxford since 1884 with wife Ada and eleven children, some named to indulge his interest in ancient languages.12 He employed some of them at his Oxford garden studio with a team of assistants to check slips sent to him for inclusion in the OED. The Post Office even installed a special post-box by his house for submissions.

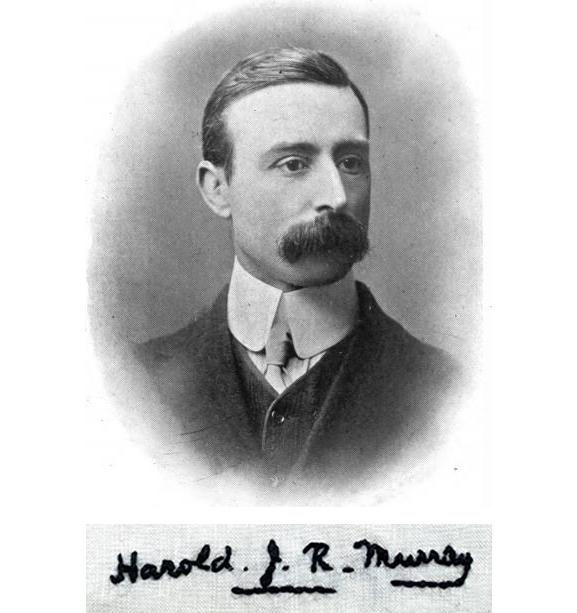

The Roses clearly knew this family well, as seven of the Ruthven-Murray offspring are also present on Gertrude Mabel’s tablecloth. The eldest, Harold James Ruthven Murray, was an Inspector of Schools who became an eminent chess historian, his book still regarded today as ‘the most authoritative and comprehensive history of the game’.13

Oswyn Alexander Murray was a Private Secretary to the First Lord of the Admiralty in 1901. He was knighted in 1910 and became Permanent Secretary at the Admiralty in 1917.14 Their colourfully named brothers Ethelbert Thomas and Aelfric Charles and sisters Rosfrith Nina, Elsie Mayflower, and Hilda Mary also signed the tablecloth.

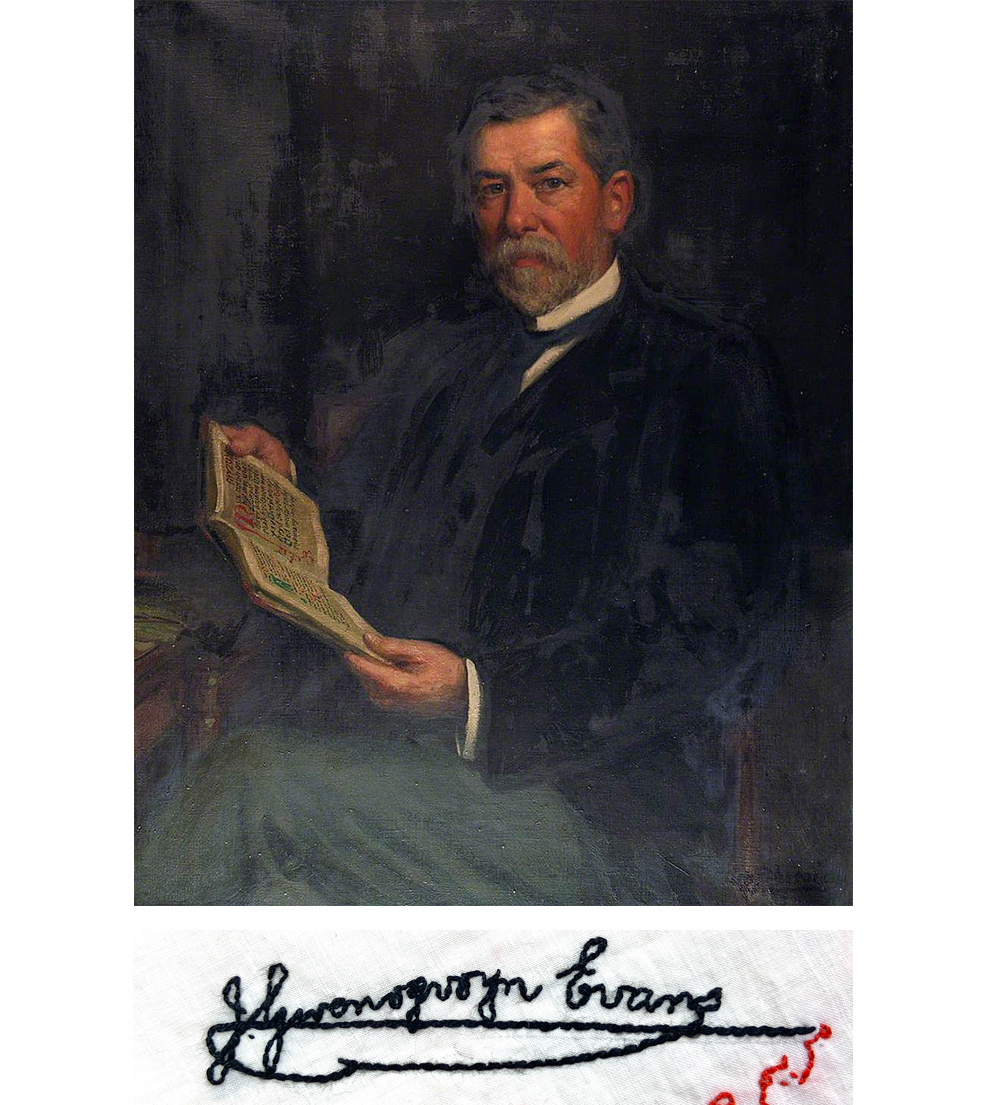

Notable Oxford residents ‘collected’ by Gertrude Mabel included John Gwenogvryn Evans, a palaeographer, literary translator, and inspector of Welsh manuscripts for the Historical Manuscripts Commission. He spoke only Welsh until he was 19, but became a Unitarian minister, moved to Oxford in 1880, and was awarded a doctorate at Oxford in May 1901 for work translating medieval Welsh texts. He was a major contributor to the founding of the National Library of Wales.15

Two others were theologian James Edwin Odgers, Professor of Theology at Manchester College, Oxford16 and Julius Sankey, a surgeon living in Oxford near the Bodleian Library.17

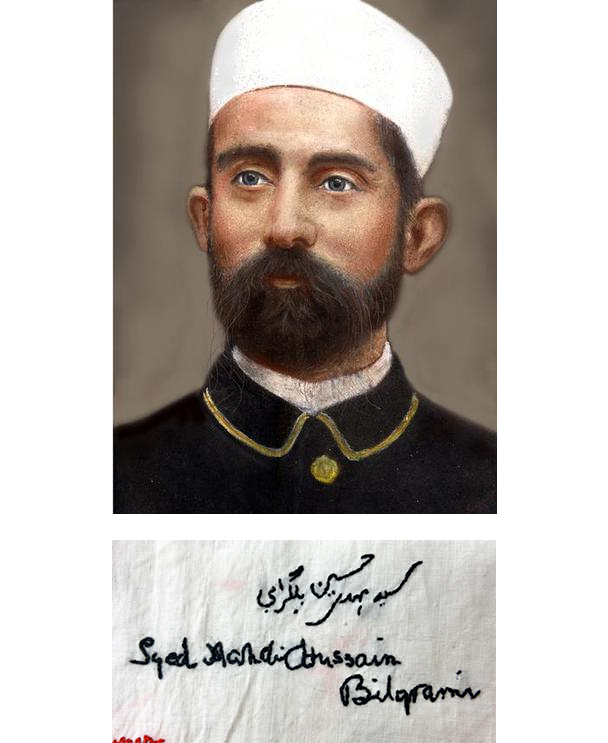

Gertrude Mabel also managed to attract people of national or international significance to sign her tablecloth, perhaps while they were visiting Oxford. Syed Hussain Bilgrami was an Indian civil servant and educationalist, who at the time of his signature worked for the Nizam of Hyderabad. He may have been in Oxford while accompanying Indian Minister Sir Salar Jung as his private secretary on a mission to England. During the visit they were ‘greatly “lionised” and feted by the best society’ and ‘had the honour of meeting and speaking with Queen Victoria and […] other distinguished people like Disraeli, Gladstone, Lord Salisbury’.18 They also, perhaps, had the honour of meeting Gertrude Mabel Rose.

He has distinguished her tablecloth by signing his name in both English and Arabic (or Urdu or Farsi), though her attempt at embroidering the latter accurately was rather unsuccessful. Bilgrami became Director of Public Education in Hyderabad, and in 1901-2 served on the Indian Universities Commission. Later he was adviser to the All India Muslim League, aiming to secure Muslim rights in India.

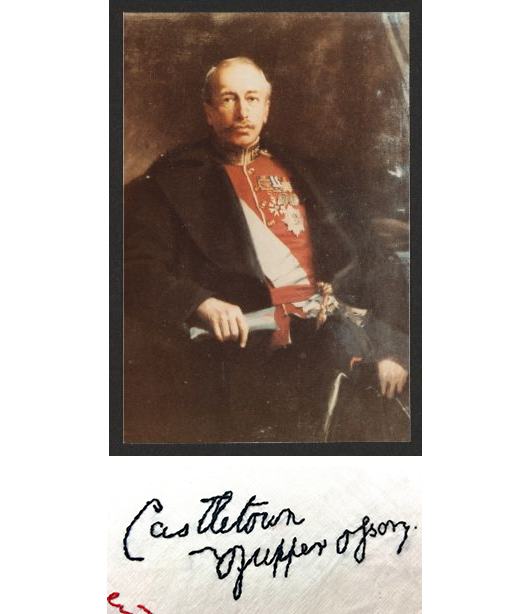

Another notable signatory was Bernard FitzPatrick, 2nd Baron Castletown. Castletown of Upper Ossory was an Anglo-Irish peer, soldier and Conservative Member of Parliament. He was educated at Eton and Brasenose College, Oxford.

In February 1900 he left on special service during the Second Boer War, for which he was knighted in May 1902. His autograph must have been a ‘prize’ for a middle-class merchant’s daughter from Oxford, but it’s something of a mystery how he came to sign.19

Perhaps the most colourful characters among Gertrude Mabel’s collection were the ‘creatives’. Whether they were performing in Oxford, or she pursued them elsewhere like a true autograph hunter, their signatures and their stories are the most idiosyncratic.

Harriet Hope Glenn was an American opera singer and music teacher born in Iowa. She was a trained contralto and had good initial success singing opera and oratorio in the USA, France, and England. She counted among her friends Sir Arthur Sullivan (of Gilbert and Sullivan fame) and Sir Charles Hallé, founder of the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester. However, after an unsuccessful marriage failed, she found she couldn’t support herself by singing.

Highlighting the difficulties of a professional woman alone at the time, she hints at her distress in a telling interview in The Sketch in 1895, with accompanying photograph. Asked why she wasn’t performing so much, ‘The sweet singer smiled sadly’, explaining ‘The last six years of my life have been so overwhelmed by sorrow that I have had no heart to put the necessary spirit and enthusiasm into my work’.20 By the 1901 Census, aged 38, she was living in Marylebone in London, described as a teacher of vocal music. According to experts quoted by a recent USA historian, Hope had a ‘rarely beautiful contralto voice’ with ‘great flexibility and power’. She was ‘winsome of face [with] graceful physical presence’ and was ‘a celebrity in 19th century opera houses in America and across Europe’.21

Was she performing at a theatre in Oxford? We’ll never know how Gertrude Mabel met her or if she actually did, but Hope has literally taken ‘centre stage’ on the tablecloth. It’s hard to imagine that this demonstrative and incongruously large signature emblazoned right across the middle of the cloth isn’t evidence that it was signed in person. Harry Furniss makes an apt comment in his article in The Strand in 1902: ‘nearly all actresses write a bold hand. Talk of “filling the stage”, I cannot recall any of our charming actresses – particularly those hailing from America – that would not fill a paper equal in size to the largest stage with their autograph alone!’22 Perhaps Hope was at a social gathering where the cloth was being signed? If they witnessed such showmanship, imagine the reaction of Maida the future missionary or the Indian politician!

Alicia Adélaide Needham was an Irish composer of songs and ballads and a Suffragette, but unlike Hope Glenn she achieved success with support from her physician husband. She was the first woman conductor at the Royal Albert Hall in London, a Suffragette, and in 1906 the first woman president of the National Eisteddfod of Wales. In 1902 at about the time she signed the tablecloth, Alicia had won a national competition to write a song for the Coronation of King Edward VII. However, once her husband died in 1920, Alicia was forced to sell most of her possessions and never composed anything again.23

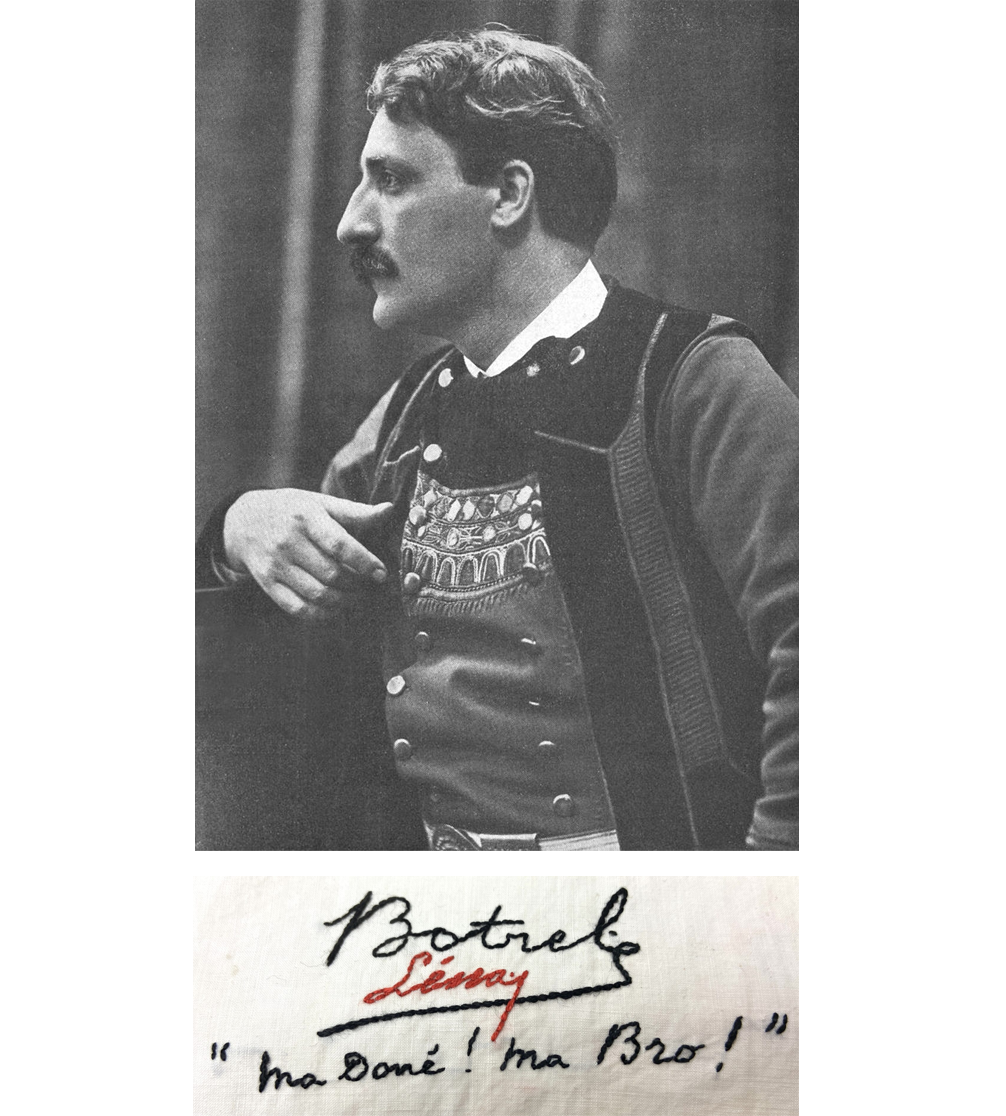

Finally, meet singer-songwriter, poet, and playwright Théodore Botrel; born in Dinan in 1868, he specialised in Breton popular songs.24 Botrel signs the tablecloth ostentatiously with his surname, the place name Léssay in Normandy, and the phrase ‘Ma Doné! Ma Bro!’ The meaning of his exuberant quote is unclear. Though ‘Ma Bro’ is Breton for ‘My Country’, ‘Ma Doné’ appears difficult to translate.25

From his photos, it is clear that Botrel wanted to make an impression. Later in his career he sang for WWI troops in France, when The New York Times of 18th July 1915 said of him: ‘Even before he opens his mouth you are interested and attracted by his noble and frank bearing. His features are of classical regularity, his complexion pale, his forehead wide and high like that of a deep thinker. Beneath a thick moustache one sees clean-cut lips, and his eyes, keen and penetrating, also have a faraway look’. 26

Botrel himself was a great self-publicist. His friend Émile Hamonic produced a series of postcards with scenes from Botrel’s songs and plays, photos of the great man and his signature, which were widely circulated. Did Gertrude Mabel trace from one of these postcards? The tablecloth signature is certainly very like that on one card showing him in Breton costume, complete with that wonderful ‘thick moustache’ and ‘faraway look’.

In 1904 Botrel was the Breton representative at a Pan-Celtic Congress in Caernarfon and could have performed or visited Oxford, so perhaps Gertrude Mabel did actually meet him. If she did, we have to hope she heard him perform. His songs are still being sung and recorded.27

The tablecloth was donated to the Royal School of Needlework by Gertrude’s descendants in 2009. Though autograph tablecloths were commonplace in the Edwardian era, they were perhaps regarded as ephemeral at a later date and not many seem to survive in published public collections. In the UK there is one of similar date in the Garrick Club collection in London, and another incomplete example with famous actress Ellen Terry’s signature in the Victoria and Albert Museum. One more is listed online as being at the Embroiderers’ Guild of South Australia and another particularly exceptional example, which includes the signature of early Royal School of Art Needlework designer Walter Crane, is in the Te Papa Tongarewa, the Museum of New Zealand.28 Given the numbers once produced there should be more survivals, but for now Gertrude Mabel’s smart autograph tablecloth in the RSN collection provides a fascinating insight into the people and textile pastimes of a former era.

Bibliography:

1 RSN Collection (COL.2009.26).

2 ‘Anglican Parish Registers’, Oxfordshire Family History Society, reference number: PAR196_ACC5614_1. ‘Oxfordshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1930,’ Ancestry.com, accessed 19 February 2024, https://www.ancestry.co.uk/discoveryui-content/view/2498362:7814?tid=&pid=&queryId=a15affca-34ef-4e8d-bdb2-9a2ffe9a5252&_phsrc=FlR13&_phstart=successSource.

3 Hunter Dukes, ‘The Autograph Fiend’, History Today, 25 March 2021, https://www.historytoday.com/miscellanies/autograph-fiend.

4 Harry Furniss, ‘The Autograph Hunter’, The Strand Magazine 24, July-December 1902, p. 542. Accessed via the Internet Archive from an original at University of Michigan, https://archive.org/details/TheStrandMagazineAnIllustratedMonthly/TheStrandMagazine1902bVol.XxivJul-dec/page/n549/mode/2up.

5 Hunter Dukes, Signature: Object Lessons (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), p. 54.

6 The Graphic: an Illustrated Weekly Newspaper, 20 January 1900, p. 4, Newspapers.com, accessed 19 February 2024, https://www.newspapers.com/image/393823619/?terms=Autograph%20tablecloth&match=1.

7 Coventry Herald and Free Press, 19th October 1900, p. 3, Newspapers.com, accessed 19 February 2024, https://www.newspapers.com/image/790266322/?terms=Autograph%20tablecloth&match=1.

8 Manchester Evening News, 18th November 1904, p. 6, Newspapers.com, accessed 19 February 2024, https://www.newspapers.com/image/800889199/?terms=%22Autograph%20tablecloth%22&match=1.

9 The Cornishman, 7th January 1904, p. 6, Newspapers.com, accessed 19 February 2024, https://www.newspapers.com/image/786607515/?terms=Autograph%20tablecloth&match=1.

10 Press cutting from unidentified source, Sheffield Archives Ref No. s08296 (copyright www.picturesheffield.com, non-commercial licence obtained. Not to be reproduced commercially without licence, though can be cited in social media with reference).

11 ‘Rev Duncan Gordon McNaughton Leith’, Find a Grave, accessed 19 February 2024 https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/179529614/duncangordon_mcnaughton-leith.

12 ‘James Murray (lexicographer)’, Wikipedia, accessed 19 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Murray_(lexicographer).

13 ‘H. J .R. Murray’, Wikipedia, accessed 19 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H._J._R._Murray.

14 ‘Oswyn Murray (civil servant)’, Wikipedia, accessed 19 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oswyn_Murray_(civil_servant).

15 ‘John Gwenogvryn Evans’, Wikipedia, accessed 19 February 2024,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Gwenogvryn_Evans.

16 Various Ancestry.com records, including the 1901 census, 1903 and 1907 Kelly’s Directory of Oxfordshire, and 1914 banns of marriage of his son, Paul. University records list his colleges as University College London and Manchester College, Oxford.

17 ‘Nos. 26–27: Blackwell’s Booksellers’, Oxford History, accessed 19 February 2024, https://www.oxfordhistory.org.uk/broad/buildings/south/26,27.html.

18 G.A. Natesan, Eminent Mussalmans (Madras: G.A. Natesan & Co., 1925), p. 358. Accessed via the Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.172559/page/n7/mode/2up. ‘Syed Husain Bilgrami’, Wikipedia, accessed 19 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syed_Hussain_Bilgrami.

19 ‘Bernard FitzPatrick, 2nd Baron Castletown’, Wikipedia, accessed 19 February 2024,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernard_FitzPatrick,_2nd_Baron_Castletown.

20 ‘A Sweet Singer – Ten minutes with Madame Hope Glenn’, The Sketch: a Journal of Art and Actuality, 10th July 1895, p.578. Accessed via Hathi Trust from an original held by the University of Minnesota, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951002800406d&seq=466. ‘Hope Glenn’ Shigo Voice Lessons, accessed 19 February 2024, https://shigovoicelessons.com/voicetalk//2011/05/hope-glenn.html.

21 Cheryl Mullenbach, ‘Iowan’s Life As Professional Singer In The 1800s: Not All Wine and Walnuts’, Investigate Midwest, 26 August 2017, https://investigatemidwest.org/2017/08/26/iowans-life-as-professional-singer-in-the-1800s-not-all-wine-and-walnuts/.

22 Harry Furniss, The Strand Magazine: An Illustrated Monthly XXIV, July-December 1902, p. 545. Accessed via the Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/TheStrandMagazineAnIllustratedMonthly/TheStrandMagazine1902bVol.XxivJul-dec/page/n549/mode/2up.

23 ‘Alicia Adélaide Needham’, Wikipedia, accessed 19 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alicia_Adélaide_Needham.

24 ‘Théodore Botrel’, Wikipedia, accessed 19 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Théodore_Botrel.

25 ‘Basic Celtos’, Lyrics Translate, accessed 19 February 2024, https://lyricstranslate.com/en/ma-bro-ma-bro.html.

26 ‘Botrel, the Trench Laureate’, New York Times, 18 July 1915, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1915/07/18/104015161.pdf.

27 ‘Théodore Botrel Lyrics’, Sonichits, accessed 19 February 2024, https://sonichits.com/artist/Th%C3%A9odore_Botrel.

28 The Garrick Club Collections (M0142), https://garrick.ssl.co.uk/object-m0142. Victoria and Albert Museum (S.287-1984), https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1113770/autographed-tablecloth-tablecloth/. Embroiderers’ Guild of South Australia Museum (2018-012), https://embroiderymuseum.org.au/object/918012/. Te Papa (PC000204/), https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/1584098.