Travel across the Atlantic to Barbados to learn more about the world’s oldest known Barbadian sampler, which is in the RSN Collection. Though Martha Collymore’s 1771 sampler looks nearly identical to samplers made in England in the 17th century, it is actually an important insight into the needleworking lives of British settler families in Barbados in the 18th century. Read on to learn more about this historically significant piece of Caribbean material culture

Isabella Rosner is the curator of the Royal School of Needlework, where she leads on digitising and cataloguing the Collection and cares for the RSN’s many historical textiles

An article about this discovery with additional information can be found in the February 2025 issue of History Today.

The Royal School of Needlework Collection includes a wide variety of samplers that span the 17th through 21st centuries. The vast majority of them were made in Britain, with the occasional example made in continental Europe. One sampler in the RSN Collection was made many thousands of miles away, in Barbados. It is one of only three samplers in any public collection thought to have been made on the island in the eighteenth century.

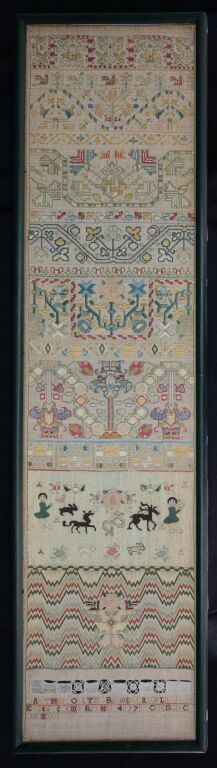

Figure 1: Martha Collymore, sampler, Royal School of Needlework Collection, RSN.1229.

Though the sampler (RSN.1229) looks very much like a seventeenth-century English band sampler, it was actually made on the other side of the Atlantic approximately a century later. This sampler is the work of Martha Collymore in 1771. The sampler, worked in polychrome silk threads on unbleached linen, features several typical seventeenth-century bands, including stylised carnations and Celtic knots, a menagerie with clothed ‘boxers’, and roses and pinwheel-shaped flowers. At the very bottom is an inscription which reads, ‘MaRTHa COLLYMORe HeR SaMPLaR ENDed DeCeMBeR THe 24 1771 MC IC SC KC IW MW’. The sampler retains strong colour, with the original, bright colours visible on the back. It differs from its seventeenth-century counterparts in its use of detached buttonhole stitches for various flower petals and in its final embroidered band, which shows a rose flanked by two birds and a Bargello work background.

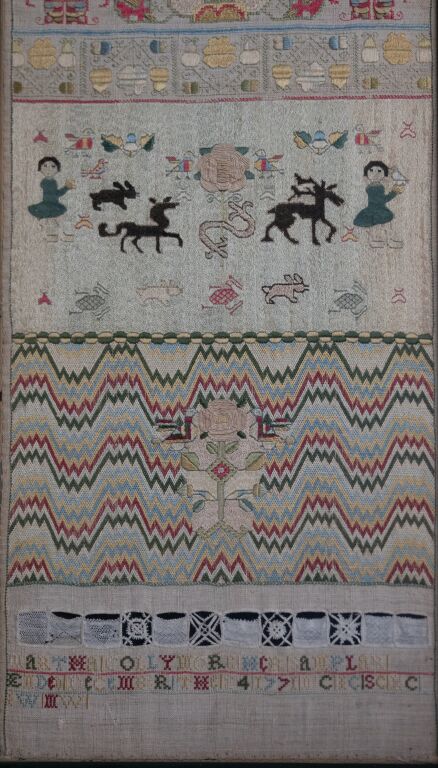

Figure 2: Detail of Martha Collymore’s sampler, Royal School of Needlework Collection, RSN.1229.

We can identify this work as being made in Barbados because of this singular band, as only one other sampler in a public collection is known to have a similar design. This sampler was made by Jane Rollstone Alleyne in 1777 and is now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (T.24-1940). Though it is shorter than the Collymore sampler and features different bands, it, too, is an eighteenth-century sampler with seventeenth-century style bands. More importantly, it, too, features an analogous Bargello band with a rose at its centre.

Jane Roll[e]stone Alleyne was born in Barbados in 1767, born on 31 December and baptised on 10 March 1768 in St James parish. These genealogical details can be confirmed not only by records but also by the inscription ‘10’, her age, at the bottom of her sampler. The full inscription reads, ‘JANE ROLLSTONE ALLEYNE 10 1777’. Alleyne was the daughter of John Holder Alleyne and Mary Ann Alleyne (née Skeet). The Alleyne family had been in Barbados for over a century at this point and were, as plantation owners, heavily invested in the institution of slavery.

Alleyne married her cousin, Abel Alleyne, by whom she had a daughter named Marian Skeete Alleyne. She died on the 18th of March 1838 in Aldersgate Street, London. Though records confirming this have not yet been found, it seems likely that Alleyne did not move to London until later in life. Her daughter was married in Barbados in 1810. Though it is not known where and by who in Barbados Jane Rollstone Alleyne was taught, it can be assumed that her teacher was taking inspiration from old samplers brought to Barbados from England. The similarities between the Alleyne and Collymore samplers suggest they were taught by the same teacher. This anonymous teacher was clearly skilled and had high standards for her students, making both Alleyne and Collymore created three-dimensional flower petals, which were rare in seventeenth-century samplers and essentially non-existent in eighteenth-century examples.

Though none of Martha Collymore’s genealogical records have yet been found, it is likely she was born in Barbados around 1760. A John Collymore was born to Samuel and Martha Collymore (née Wilson) on 25 December 1758 and baptised in St Phillip parish, Barbados in October 1759. Given the timing of John’s birth and the initials on Martha’s sampler, it is likely that John was Martha’s brother. This family tree links up exactly with the family initials on Martha’s sampler: ‘MC’ is Martha Collymore, the sampler making Martha’s mother; ‘IC’ is John Collymore, her brother; ‘SC’ is Samuel Collymore, her father; ‘KC’ has not been conclusively identified but is likely Katherine Collymore, Samuel Collymore’s sister living in the same parish; ‘IW’ is John Wilson, Martha’s maternal grandfather; and ‘MW’ is Mary Wilson, her maternal grandmother. Martha Wilson, Martha Collymore’s mother, was indeed the daughter of John and Mary Wilson. Samplers of this period often feature pairs of family initials, commemorating siblings, parents, and grandparents. A Martha Collymore was buried in St Phillip parish, Barbados on 15 September 1779 – could this be the Martha who made the RSN sampler? It is possible.

Like the Alleynes, the Collymores were an old slaveholding, plantation owning family in Barbados. It is likely that Martha Collymore was a relation, perhaps a cousin or even a niece, of Robert Collymore, who was known for his relationship with one of the women he enslaved. Amaryllis Renn Phillips, later Collymore, gained her freedom from her relationship with Robert Collymore, which led to her successfully running several plantations. She was, at the time of her death in 1828, the richest free Black women in Barbados. It is currently not possible to ascertain the exact relationship between Martha Collymore’s branch of the family and Robert Collymore’s due to a lack of available digital genealogical information.

Figure 3: Detail of Martha Collymore’s sampler, Royal School of Needlework Collection, RSN.1229.

Not only are the Alleyne and Collymore samplers extremely rare and significant, they are especially early examples of samplers made in British colonies outside of what became the United States. The Barbados Museum and Historical Society is in possession of two nineteenth-century Barbadian samplers. These samplers provide insight into the education of girls from slave-owning families in the Caribbean, contributing to the increasingly popular field of scholarship of Caribbean material culture. This discovery will be of interest not only to sampler and embroidery enthusiasts, but also scholars of girlhood, race, and the Atlantic world.

An article about this discovery with additional information can be found in the February 2025 issue of History Today.